New Delhi -- If the Devil's greatest trick is pretending he doesn't exist, India's greatest political trick has been pretending it has a minimum wage when it really doesn't. And the consequences are quite Dante-esque. Two-thirds of Indians and their families -- some 750 million people -- live in a state of perpetual purgatory because they earn less than $2 per-person-per-day, the World Bank's definition of poverty.

Original Article

Source: huffingtonpost.com/

Author: Jehangir S. Pocha

For 67 years successive Indian governments have created Byzantine anti-poverty schemes costing billions of dollars to help these "wretched people." But despite India being in the midst of a general election, no party is pushing for the one thing that would combat poverty without bankrupting the exchequer -- getting businesses to pay workers a living wage.

All parties are promising voters they will create millions of new jobs. But they are silent on how these jobs will pay a pittance, keeping workers locked into poverty -- a poverty that makes big money for big business, which loves to exploit cheap workers, and big government, which loves to expand anti-poverty programs for officials to milk.

Apologists for the status quo can justly claim India has had a Minimum Wages Act since 1948 and that it establishes a national floor wage and mandates states set minimum wages in different industries. But the law is among India's most complicated and worst implemented.

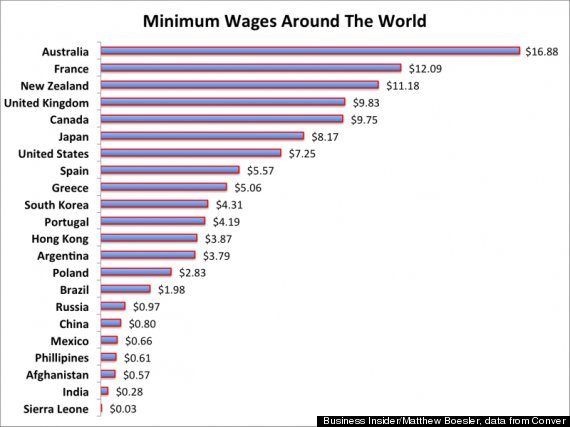

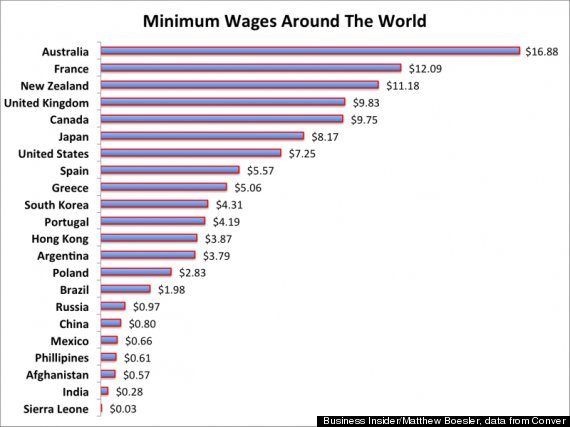

India's official minimum wages are among the lowest in the world, even lower than Afghanistan's:

The amounts range from a shameful Rs. 38 ($.63) a day for tea planters in northeastern Tripura state to Rs. 215 ($3.60) a day in northwestern Haryana.

Many workers do not even get these puny amounts because businesses routinely flout minimum wages with impunity. Most workers do not even know minimum wages laws exist, and local governments that spend huge amounts on ads asking people to keep cities clean make no effort to educate workers about them.

Underlying this is the uncomfortable truth that too many Indians are inured to the exploitation of workers. This was brought into sharp relief when a junior officer in India's New York Consulate, Devyani Khobragade, was arrested in January for paying her Indian nanny less than one-third of New York's minimum wage.

Instead of being upset and embarrassed that a foreign government had caught an Indian diplomat underpaying her Indian nanny, most Indians and New Delhi did not really understand what the fuss was all about. They felt the real slight to India's national honor was that Khobragade's was strip-searched after being arrested. She became a national heroine while the maid, Sangeeta Richards, faced a long list of accusations, including ungratefulness for not appreciating how Khobragade gave her free time to watch TV.

This social assumption that "they" are inherently different from 'us' and do not have to have access to things like decent housing, clothes, food, leisure, education and health care is etched into the Indian psyche.

The minimum wage is barely taught even in schools and rarely discussed by government, industry and even media. Though India has made the United States its rolemodel in many ways and follows American politics, diplomacy, TV shows and school shootings with great zeal, America's currently raging debate over raising the minimum wage is hardly being covered in the Indian media.

From time immemorial, exploitation has been the basis of the Indian economy as evidenced by the caste system, landlordism, and the feudal structures India's successive rulers embraced. Even today, from the top 1 percent to the lower middle-class, almost every Indian home and business depends on underpaid labor, whether a factory worker or a housemaid, for their comfort.

Businessmen and professionals celebrating the benefits of reforms with unbridled ambition and ostentation may pat themselves on the back for being India's wealth creators. But beyond the raucous Bollywood songs that have become the anthems of this ebullient generation, there is a total denial of the fact that it is India's under-paid, under-skilled and under-appreciated workers who are carrying the economy on their shoulders.

The hard fact is that there is hardly a single Indian company that would be globally competitive if it paid global wages. With India's costs of power, land, capital, transport and logistics and technology being among the world's highest, businesses see cheap labor as the easiest way to be competitive. Developing the efficiencies and innovation in design, business processes and technology that create real global competitiveness is beyond the grasp of most Indian businesses.

Predictably, even the rare word about raising workers' wages is drowned out by cries from business groups and economists. They say it is fallacy to suggest Indian workers are underpaid because their wages are determined by the market. Since India has hundreds of millions of poor workers, they argue, their wages will naturally be very low. They also argue that raising the minimum wage will distort the free market for labor and cut job growth.

But the fact is that there is no free labor market in India and has never been. Free markets operate on certain assumptions, such as participants having ready access to information, equal access to opportunity and the ability to make free choices. Not only are Indian workers denied these choices, enshrined social justices ensure their daily realities are diametrically the opposite, a much greater distortion of free market principles. Creating a sensible minimum wage as a way to correct these historical wrongs is no longer a 'Leftist' idea; it is merely common sense.

Even if this leads to a 10 percent cut in new job growth, having 90 decently paying new jobs is preferable to 100 deprivation wage ones.

The very entire premise that higher minimum wages will hurt job creation is also open to challenge. Robert Reich, who was labor secretary under President Bill Clinton, argues that after he raised the minimum wage in 1996 "the U.S. economy created more jobs in the next four years than were ever created in any four-year period."

It could be said the boom Reich talks about was driven by other factors, but the argument that higher minimum wages will kill job growth is largely a concern in the West where salaries and unemployment are already high. There is no evidence this will happen in India where labor unemployment is a scant 2 percent. The demand for workers here is so high and their wages so low that businesses will likely absorb the cost or simply pass it on the consumers.

The larger truth is that Indian businesses and families facing rising costs of things they cannot control, such as raw materials and food, simply look to balance their budgets by using their social, economic and political power to control the one cost they can control, labor. That is why the same husband who wordlessly coughs up Rs. 1 lakh for a Louis Vuitton handbag quibbles when the maid asks for a Rs. 500 raise.

Apart from the moral shame, this is an economic catastrophe.

Reich and other economists argue that radically underpaying workers kills the incentive to work, keeping workers away from jobs and dependent on government handouts -- and leads them towards petty crime.

Even those who do work despite measly wages remain poor and demanding more benefits, sops and subsidies from government. By paying those same workers better, they can be turned into real consumers whose spending will boost GDP. This is something that has already been evidenced when India experiences good rainfall and harvests and rural incomes rise. Rural spending also rises, pushing up GDP and company profits. The government's creation of a rural job guarantee scheme has also done wonders to increase rural incomes and bolster the rural economy.

President Barack Obama recently made this case by quoting Henry Ford, who paid his workers well so they "could afford to buy the cars they were building."

This is a far cry from India where even middle-class people can afford a chauffeur because he earns less than the monthly cost of his car's petrol or its monthly payment.

It is time to replace such exploitative selfishness with enlightened self-interest. India will only ascend to true democracy and development when all citizens have the right to the same quality of life and to work and live with dignity.

Setting minimum wages at about Rs 7,000 ($116) a month for workers in rural areas and Rs. 10,000 ($166) a month in cities, and actually implementing them, is the easiest way to further this without bankrupting the nation with more leaky anti-poverty schemes. In fact, raising and enforcing decent minimum wages could help the government cut back on several of its existing anti-poverty schemes.

While these new minimum wages will not apply to many of India's rural poor who toil on their own tiny parcels of land, they must apply to all India's 200 million workers. Currently, India's labor laws only apply the 20-25 million workers in what is called the "organized sector," which includes registered corporations and businesses.

New higher minimum wages must also be made to apply to the other 175 million workers who work in the unorganized or unincorporated sector, as farm hands, pushcart vendors, construction workers, private security guards, household help, drivers, shoe shiners, waiters, shop help etc. Currently, this is not happening.

For this, local governments must totally overhaul the way labor department's work and get them to proactively monitor prevailing wages. NGOs can also play a crucial role in this and help workers who want to complain about being underpaid. Once workers become more aware of their wage rights and are helped in obtaining them, they will find ways to get them.

To balance the benefit to workers who get hired, the government should also support businesses by making it easier for workers to be fired. Ironically, while India has virtually no laws governing what workers must be paid, it has rigid laws virtually prohibiting the layoff of any workers in the organized sector. These anti-retrenchment laws are so draconian and senseless that they have achieved little other than strangling business and driving away foreign investment. Lifting or easing them will give business greater leeway in managing their labor forces and bring greater moderation to all sides of the labor market, hiring, paying and firing.

This simple common sense trade-off can help India secure its economic future while also helping achieve the greater social harmony and natural justice to which 1.2 billion people aspire.

Original Article

Source: huffingtonpost.com/

Author: Jehangir S. Pocha

No comments:

Post a Comment